Students of sitcom writing courses are taught to take their hapless central characters and have them do something that makes life worse for themselves. With hilarious consequences. And then have them do something that makes things even worse. Watch any great sitcom from Fawlty Towers to The Office and, indeed, Father Ted and you will see the pattern.

The deep irony that runs through Graham Linehan’s important memoir is the way in which his story resembles this narrative cycle – something he writes about at some length when covering the craft of sitcom writing – only without the joke. There is, admittedly, some grim humour about his first major descent into public opprobrium on Twitter and beyond. Coming round from an operation to have a testicle removed (this sounds like a set-up for a punchline but is indeed what happened) and under the influence of some powerful (presumably opioid) pain-reduction medication, Linehan picked up his phone, opened Twitter and made one or two typically pithy comments before succumbing once again to sleep. When he next woke up, his life had changed.

At the risk of coming across a bit meta, I would argue that Tough Crowd is at least as much about narrative arcs as it is about the destruction of a decent man’s livelihood, reputation and domestic happiness by the cultural Marxist mob. Indeed, the first half of the book - charting as it does Linehan’s career from solitary Irish adolescence to music reviewer and, finally, comedy writer and director – is all to do with learning his craft. His post-punk music reviews for a small Irish magazine Hot Press were deliberately spiky and personal, so much so that when he took a similar job in London, he quit before even starting on finding out that his new employer’s house style forbade the use of the word ‘I’. Perhaps it was this training that enables him to describe pronouns in Twitter bios as “cat bells for idiots”. This isn’t exactly Lawrence of Arabia but I couldn’t help seeing Linehan’s career journey as the perfect rehearsal for where he now finds himself.

The second half of the book is a painful read and one can only imagine what it was like to experience it. Linehan told The Daily Telegraph that he had to dispose of his first draft because it was too angry. It would have been the easiest choice in the world for him to back away from Twitter rows with social justice warriors and yet his natural stubbornness appears to have melded with his deep-seated sense of decency. This decency is partly explained by his touching descriptions of his family background: a loving couple for parents and a father who told him to stand up for women and not to be like James Bond. In the throes of having his life ripped apart around him, he simply asked when questioned why he persisted in supporting the rights of biological women: “I will not abandon my daughter.”

Given Linehan’s attachment to his parents and children, the fragmentation of his family is particularly hard to read. If anyone doubts that the cultural Marxist mob really is out to destroy its enemies, read the description of Linehan’s loss of his livelihood and his wife’s (spoiler alert: soon-to-be-ex-wife) distress at activists targeting their house. In the fall-out from Linehan’s destruction, many people do not come out well. While not quite in Rowling territory as far as wealth goes, Jimmy Mulville has done very well indeed out of Hat Trick Productions (due in part to the success of Father Ted) but chose not to stand up for Linehan when given the opportunity.

Graham Linehan’s resilience is remarkable and I wonder how many others in the same situation could have written a final chapter titled “Green Shoots.” He finds optimism in the allyship he has found, particularly among gender critical feminists and appears more appalled at their poor treatment than at his own. He surgically takes apart the mob’s misogyny, pointing out as one of many examples the abuse of Hibo Wardere, the Somali-born author and activist that has spent her life campaigning against female genital mutilation. In a further slightly meta turn, he describes efforts by campaigners to get the publishers of the book to pull out.

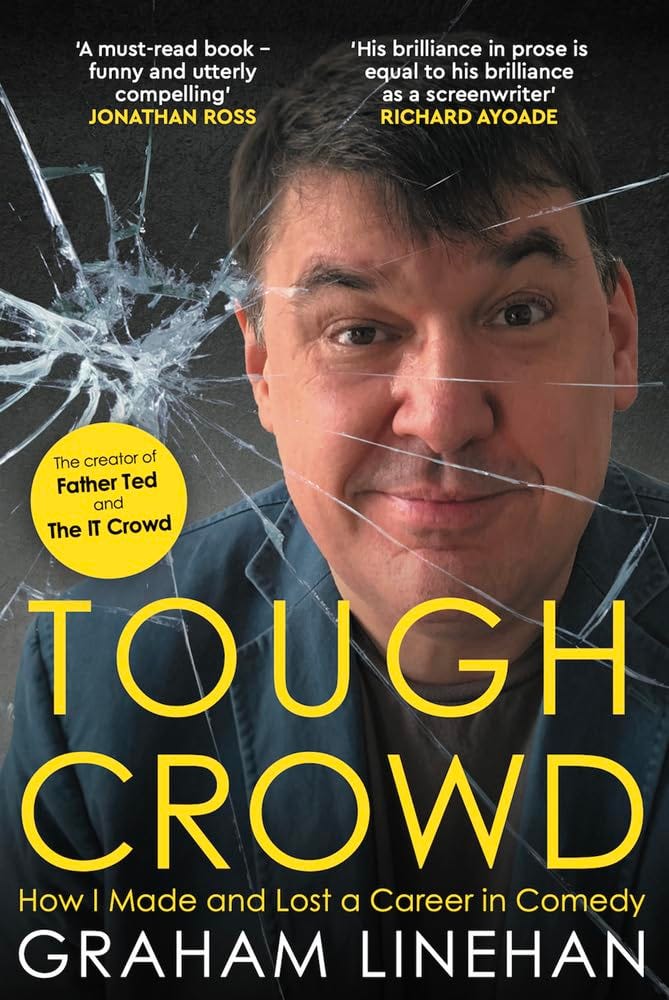

Even following the book’s publication, Jonathan Ross and Richard Ayoade were lacerated on social media for their endorsements on the book’s cover: “Well that’s Richard Ayoade in the bin,” posted India Willoughby on X, “along with already confirmed terf Jonathan Ross. What is wrong with these people?” Both have survived the bin, it seems, suggesting that there might be something in Linehan’s optimism.

Linehan continues bravely to resist efforts to silence him, notably performing outdoors in Edinburgh after two Fringe venues cancelled a planned stand-up show by Comedy Unleashed. Comedy Unleashed, co-founded by Andrew Doyle and Andy Shaw, has since staged sets from Linehan at the Backyard Comedy Club in Bethnal Green to the audience’s huge pleasure. Is it hoping too much to see Tough Crowd as marking the high-water mark of cancel culture in the UK? While his life may not travel full circle back to the status quo like that of Father Ted Crilly in episode after episode, one can at least hope that this brave and principled man can derive some happiness from the support he has so consistently provided to others.